Archive for the ‘leadership’ Tag

Ecological Rally Part 1

photo courtesy of Michael Roberts

I thought I should write a post about the ecological rally I am setting up in Ciudad Guzmán, as it is the major project I am currently involved with. This will be the first post of what may turn out to be a number of posts about the rally, especially focussing on some of the organizational and cultural issues involved in the setting up of an event like this.

2009 is the third year that the ecological rally has been organized. The idea initially arose when I was teaching a Diploma on ‘Leadership and Sustainable Development’ at the Ciudad Guzmán regional campus of the University of Guadalajara. One of the participants on the programme, who was also a friend, was organizing a ‘rally’ to promote his language school. This seemed to involve groups of young people haring around the city in pick-up trucks, doing entertaining tasks in different locations, and making a lot of noise and creating a lot of rubbish in the process.

I suggested to my friend that he consider organizing an ecological rally, which as well as helping promote his language school, would also serve as a medium for environmental education for both the young people taking part, and the population of Ciudad Guzmán.

Banner promoting the ecological rally 2008

The first ecological rally took place in June 2007. As, by then, I was living and working in Cuernavaca, 600 kilometers away, I participated from a distance as a consultant for the rally. Last year, when I returned to live in Ciudad Guzmán, I was very involved in the organization of the rally from January through April, but suddenly had to return to England at short notice for family reasons, so I missed the actual event of the rally on the 8th June – organized to coincide as closely as possible with the International day of the Environment on 5th June.

Before I went away to England, at times, I felt despairing about the organization of the rally. It was an enormous amount of work, involving:

- Coordinating and liaising between the University, the local government, the state government and private businesses; this kind of collaboration between organizations is never easy in Mexico.

- Looking for sponsors to provide funds for the rally in return for being given publicity.

- Arranging to visit every classroom of all the secondary and high schools in Ciudad Guzmán to invite the young people to participate in teams of ten people.

- Making contact with journalists and local TV stations to publicise the rally.

- Organizing the complicated logistics of both the day of the rally on June 8th, and also la eliminatoria, a day two weeks prior to the rally in which the 22 teams who had registered to take part were whittled down to the ten teams who actually took part on the day of the rally. As part of the eliminatoria, each team had to collect used batteries to prevent then going to the municipal rubbish dump, and one of the great successes of the rally was that over 360 kilos of batteries were collected.

photo of school workshop courtesy of Michael Roberts

- Setting up workshops in a number of schools on recycling which also served to promote the rally.

I was working initially with a group of five students from the university. I requested that three students were assigned to me, to carry out their servicios sociales – around 400 hours of community service that every student at the university has to do as part of their degree course. This is potentially a way that the university could make an enormous contribution to the community in which it is located, but often the hours of servicios sociales get reduced to acting as an administrative assistant (doing photocopying, running errands etc.) to a professor at the university or a functionary in local government. In this way, for both the students and the University, the work becomes devalued.

The two other students, from the two-year course in Alternative Tourism, were doing their prácticas profesionales, which is work experience, and needed to complete this in order to graduate from their course. At least in their case, rather than being assigned to me, I had the opportunity to interview and select them.

I had hoped – rather naively in retrospect – that these students would show initiative, be committed to the rally and enthusiastic and creative in their work. What was initially disappointing, however, was that they were very reluctant to take any initiative or responsibility, and relied on me to give them detailed direction. They often arrived late at meetings, or sometimes not at all, usually without letting me or each other know in advance. For them, any other activity would generally take precedence over their servicios sociales or prácticas profesionales.

I quickly realised that they had no expectation nor much experience of working as a team, especially in the context of one person, myself, being an adult and a Professor at the University – in short, the authority figure – which created relations of dependency that are very typical in Mexican culture. This contrasted strongly with the education of my two sons in state schools in England, where they were given training in the skills of leadership and teamwork – often through creative activities like drama.

This situation was greatly eased when my younger son, Michael, who was about the same age as the students, and doing a project at the university as part of his degree course in England, joined the team. He showed that it was quite possible to argue with and challenge me, and also helped to provide a bridge between me and the students.

The interesting thing was when I very unexpectedly had to return to England two weeks before la eliminatoria. The students were forced to take more responsibility or abandon the project. Clearly, they by now felt a real commitment to the rally, and all stepped up, with the help of my friend from the language school who was one of the main sponsors, to complete the rally, which ended up being a great success.

photo courtesy of Michael Roberts

The day of the rally itself involved ten different activities or ‘stations’ which each team had to complete. These activities included a range of sporting, educational and intellectual challenges, such as climbing and rappel, making placards about environmental themes, and planting trees.

photo courtesy of Michael Roberts

photo courtesy of Michael Roberts

The rally concluded with a run which the local Athletics League helped us organize and a march to the center, where the prize giving took place.

We had always intended that the rally would help to promote the work the local government was doing in initiating a programme of separating waste, which came about partly as a result of a state law compelling all municipios to implement a programme of waste management. So an important purpose of the rally was to educate the young people about this, and we included the different colours of the separated waste in the different activities. In the run, for example, each person was given one of three differently coloured T-shirts with the indication of the type of waste the colour corresponded to.

In practice, it was difficult to work with the local municipio. On the final day of the rally, at the prize giving, the local government officials took control, substituting one of their people for the person from the rally who was going to act as the M.C. and claiming that the rally was an initiative of the local government. Perhaps this was an education in realpolitic for the students, though I suspect they knew all this already.

We learnt a lot from both the successes and failures of last year’s rally. One heartening aspect this year, is that the two students who were completing their prácticas profesionales are setting up a rally in a school in a small town near Ciudad Guzmán where one of them lives. In addition, one of them is helping as a volunteer with the organization of the rally this year.

In subsequent post(s), I will write more about the organization of the rally this year. For more information, in Spanish, about this year’s rally, click here. Do let me know via a comment if there is anything you would particularly like me to write about.

Memorable Meals In Mexico 3: Tierradentro

Tierradentro is a cultural center and cafe located at No. 24, Calle Real de Guadalupe, one of the principal streets in San Cristóbal, a block away from the main plaza, in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. It is situated in a large, open, airy courtyard, ringed by a couple of offices and four shops selling crafts behind the portales of the courtyard.

I had walked past it a few times without entering, before seeing that it appeared in one of the five best restaurants in the New York Times list of recommended restaurants in San Cristóbal. I first ate there one evening with Lupita, a Mexican friend, with whom I was travelling in Chiapas. The food was good. Very fresh, in the style of Mexican comida casera, which translates as home-cooked food.

I ate enchilidas verdes. The green salsa was spicy without taking the roof of my mouth off, and the rolled tortillas were generously stuffed with chicken. Lupita and I shared guacamole, which was also good. My overall impression was of fresh, tasty food at very good value for money.

I noticed that many people there were using their computers – unusually, a preponderance of Macintosh’s, which might say something about the kind of people to be found here. I resolved to return the next day for lunch so I could make use of the wi-fi connection, as well as explore the menu further.

The following day, after visiting the two nearby indigenous towns of San Juan Chamula and San Lorenzo Zinacantán, I returned to the restaurant for lunch with Lupita. This occasion we both selected different versions of the menu del día. I ate sopa azteca, followed by fish in a chile chipotle sauce. Lupita also chose sopa azteca, then pescado a la veracruzana (fish cooked in a mild sauce of tomato, onion, olives and coriander).

Sopa azteca is a soup made with strips of fried tortillas, a tomato salsa, avocados and cheese. Lupita, an aficianado of many sopas aztecas, said that the soup was “en su punto”, that is to say, just as it should be. The soup was served at just the right temperature, the tortilla strips were crisp, the sauce perfectly flavoured, and the cheese exactly the right melting consistency.

I thought my fish was superb. Like the enchiladas verdes the previous night, the salsa was picante (hot) but not so hot that other the tastes are overwhelmed. The fish itself was succulent and fresh. Lupita said her fish, too, was excellent.

The cost for all this delicious food including a glass of aguafresca made with melon was 53 pesos, that is less than 5 US Dollars. The information given in the NYT web-page was that there was a fixed price menu of $30! Yet again showing that we should not believe all we read in the papers. The NYT site also said that it is a “Zapatista run cafe”. More misinformation!

Luckily, I was able to talk to Ernesto, who coordinates the restaurant, to understand the context, philosophy and administration of the center. It was this discussion that made the meal memorable. The food here is good, but what is really significant and memorable is the vision that the restaurant is in the process of realising. Ernesto is a deeply thoughtful man, who has been a committed social activist for fifteen years, and is the founder of a Human Rights Organization in San Cristóbal called CAPISE.

A few years ago, Ernesto and his colleagues in CAPISE had the idea of creating a space in the center of San Cristóbal, which would serve a number of functions.

- To be a “territorio rebelde en el corazón de San Cristóbal”. This means, loosely translated, creating an alternative presence in the heart of the city. “Territorio rebelde” has a particular significance in Chiapas as it is the name the Zapatistas give to their self-governing communities.

- It would offer good quality food at reasonable prices.

- It would be a cultural and social center, promoting activities like concerts, talks, dances, book presentations and offering a meeting venue for NGO’s.

- It would offer a space for co-operatives working in the Zapatista autonomous communities to showcase and sell high quality crafts at fair prices.

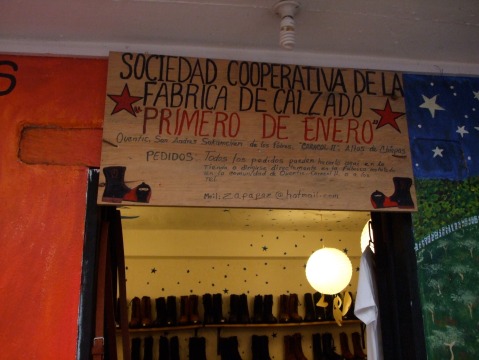

Co-operative selling boots and other leather goods

- Moreover, the profits from the restaurant could be used to help support the work of CAPISE and social projects, like providing electricity to marginalised communities.

The center has been active for nearly three years now, and has been a great success. As I talked more with Ernesto, I was struck by the complexity of the challenges and the depth of thinking involved in creating this remarkable project.

It is not a conventional business, where the primary and generally sole aim is to make a profit, although it shares with any business the need to market itself, sell its products and make a profit, or at least break even, in order to survive. As well as sharing these typical features of any business, this project is very different in wanting to offer an alternative. The following are three important aspects of this which I discussed with Ernesto:

1. The center does not sell Coca-Cola nor any of the products associated with this company and its affiliates, like Ciel in Mexico. This is for three principal reasons:

a) As a Human Rights organization, CAPISE believes that everyone should have free access to decent drinking water. Coca-Cola is actively involved throughout the world in trying to privatise water supply. It is the policy of the cafe to provide free drinking water via an ozone filter.

b) In San Cristóbal, Coca-Cola was given permission to build its factory on the slopes of the nearby Huitepec ecological reserve. This means that the company has privileged access to the water from the reserve. CAPISE has so far been unable to find out from either Coca-Cola or the local government what the company is paying for this service.

c) Mexico has the highest rate of childhood obesity in the world and the most rapidly growing rate of overall obesity. with all the negative health consequences implied by this. Many people believe this is linked to the high consumption and aggressive marketing of fizzy drinks like Coca-Cola.

Coincidentally, on the morning I left San Cristóbal and went to Tierradentro for a final goodbye coffee, a promotion for Coca-Cola was happening a few doors down the street.

Coca-Cola using traditional marketing techniques to promote its product

2. The center buys its coffee directly from co-operatives within the Zapatista controlled areas. Its policy is to buy the best organically produced café arábigo, which is usually exported to Europe, so that it is available to local people. It also believes in paying the price asked by these co-operatives without bargaining. Within this frame of reference, it is able to offer a truly excellent double expresso at 17 pesos (just over 1 USD) and sell one kg of high quality coffee at 90 pesos. Starbucks charges 160 pesos for the same quantity and quality.

3. When the center was first created it had to make a policy about how to deal with children and indigenous people coming into the cafe to sell products. Initially the center had not wanted to exclude them. However, word got around the street that this was a place in which street sellers were permitted with the consequence that many street sellers were continually coming to the center throughout the day. To deal with this, rather than exclude them, which is the policy in many San Cristóbal restaurants, it was agreed that street sellers could enter, but they could not return within a period of three hours.

To manage a project which has to survive in conventional terms as a business, but which also aims to offer an alternative to the the exploitative features of a normal commercial model, requires, in my opinion, much higher levels of leadership ability, team-working and creative thinking. It is to the credit of all at Tierradentro that they are achieving this.

As the short poem, by the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, says, that is quoted in the menus:

“La utopía está en el horizonte

Camino dos pasos, ella se aleja dos pasos

y el horizonte se corre diez pasos más allá.

¿Entonces para qué sirve la utopía?

Para eso, sirve para caminar.”

“Utopia is on the horizon

I walk two steps, it retreats two steps

and the horizon goes back ten steps further.

Therefore, what use is a utopia?

Exactly for this, that it sets the direction to walk in.”

PS For a good summary of the Zapatistas and their struggle click here on the Wikipedea article about them.

Parks and Partnership

This is Linda. Like Jimmy, who I wrote about in an earlier post, she is a Peace Corps volunteer, working with the National Park of the Nevado de Colima. Linda’s mandate, unlike Jimmy’s which was concerned with the natural resource management of the park, is the more difficult (in my opinion) task of working with the human, institutional aspects of the management of the Park. Her brief, in short, is to to strengthen the Patronato – the body which manages the National Park – as an organization. Like Jimmy, Linda is here in Ciudad Guzmán for a two year period, which will end in June this year.

Before becoming a Peace Corps volunteer, (which Linda told me had been a lengthy process of application in her case), she worked for eleven years directing a non-profit organization in Arizona, now called Silver Linings, that works with volunteers to provide help to adults. She has a Masters degree in the Management of Non-Profit organizations from Regis University in Denver, and has previously worked in the fields of literacy, battered women and mental health.

Linda and I talked about the way the park is managed from a human and organizational perspective. Continue reading

Comments (1)

Comments (1)